On the Prevention of Suicide and Self-Destructive Behaviors and Danger at Workplaces

The things that you say to a person matter greatly, especially when one brings the issue of suicide into the conversation. What you communicate matters because suicide is preventable.

Consider that if you are present at a workplace as a customer, client, worker, owner or manager, and someone commits suicide, you are likelier to be asked about what you communicated to that person and what that person communicated to you. You are likelier to be asked by a person who will be comparing answers and evaluating the situation. In a court of law or in a strong family, your communications become important for others to assess what happened and what led to the suicide.

Suicide and American Workplaces

Suicides at our Workplaces: In America, the Census of Fatal Occupational Injuries has been keeping track of suicides that occur at the workplace since 1992. The data shows that in 2016 there were 291 workers who committed suicide at their workplaces; this is the most ever recorded.

Suicides are preventable. A person’s emotional state that reaches a so-called “low point,” when the person is suicidal, can be changed through your communications. The rate of suicide for any society changes from year to year and can be lowered.

Urgent Situations for Suicide Risks: Make sure that you get involved by asking questions directly about suicide and helping the individual find immediate help when you identify these three things: (i) the person talks as if his or her situation is hopeless; (ii) the person says he or she wants to die; (iii) the person talks about killing himself or herself; or (iv) the person is looking for a way to kill him or herself (e.g., using a gun).

Serious Risk Factors of Suicide: You should also get involved or ask your Human Resources Department to get involved whenever you witness any of the following behaviors: (1) the person talks about getting revenge; (2) the person complains of feeling trapped; (3) the person talks as if he or she is a burden to others; (4) the person claims of being in unbearable pain; (5) he or she behaves recklessly; (6) he or she acts anxious; (7) the person claims he or she feels alienated, isolated or withdrawn; (8) the person displays extreme mood swings; (9) the person shows rage; or (10) he or she is getting too much or too little sleep.

The following guide has been selected from the course by William A. “Trey” Brant, PhD. and attorney William A. “Bill” Brant titled Your Guide to Ethical Conflict Management for Engineers.

Preventive Measures Guide for Ethical Conflict Management

- Know the rates of destructive and self-destructive behaviors of your State or Province.

- Know the risks of these behaviors in the industry where you work.

- Assess the risks of injuries, destructive and self-destructive behaviors in your workplace.

3.1 (a) FOR PREVENTING WORKPLACE SUICIDE: You should get involved or ask your Human Resources Department to get involved whenever you witness any of the following behaviors: (1) the person talks about getting revenge; (2) the person complains of feeling trapped; (3) the person talks as if he or she is a burden to others; (4) the person claims of being in unbearable pain; (5) he or she behaves recklessly or very impatiently; (6) he or she acts anxious; (7) the person claims he or she feels alienated, isolated or withdrawn; (8) the person displays extreme mood swings; (9) the person shows rage; (10) he or she is getting too much or too little sleep;

(b) FOR PREVENTING WORKPLACE VIOLENCE: In the US in 2016, we know that there were 18,000 assaults each week at workplaces and an annual total of 500 homicides at workplaces. You should get involved or ask your Human Resources Department to get involved whenever you witness any of the following behaviors: (1) the person talks about getting revenge; (2) the person complains of feeling trapped; (3) the person claims to be unbearably angry; (4) he or she behaves recklessly or very impatiently; (5) he or she acts anxious; (7) the person claims he or she feels alienated, isolated or withdrawn; (8) the person displays extreme mood swings; (9) the person shows rage; (10) he or she is getting too much or too little sleep; or (11) the person is insecure and searching for something dangerous, such as a knife for combat or a gun.

(c) FOR PREVENTING WORKPLACE INJURIES: In the US in 2017, 5,147 workers died from fatal injuries at work (i.e., 3.5 per 100,000). Men had a fatal work injury rate of 5.7 per 100,000 and women had a 0.6 per 100,000 rate for all full-time workers in the USA. Do you work in the automotive industry or a place where there is a risk of injuries from cars? Car accidents are the leading cause of death in workplaces. (1) Know the rate of fatal injuries in your industry; (2) Know the rate of fatal injuries in your State or location (e.g., for commercial fishing etc.); (3) Consider your age (In the US, 15% of fatally-injured workers in 2017 were age 65 or over); (4) Make sure that you are compensated for any potential risks to your health as your physical and mental well-being; (5) Understand the risks of death by the types of accidents and help improve the safety standards (info available in BLS, 2018, p. 6 & Sect. II.ii after Fig. 15).

Getting Involved in Prevention and Assisting to Find Help: As a professional, if you identify urgent situations i-iv, then you should assist the person by asking directly if he or she is thinking of committing suicide. Ask the person what is wrong. Tell the person that you understand that he or she is suffering. Aid the person to seek help. In the USA, one number for potentially suicidal or suicidal individuals is 1 (800) 273-TALK. Get involved!

Rates of Unintentional Overdoses in the United States: Another aspect of the mental health crisis of our society is overdoses. There are significantly more overdoses than suicides, according to the statistics provided by the Center for Disease Control (CDC). This problem in workplaces has been increasing more rapidly than the suicide rate, but has not reached the number of deaths of suicides.

Between 1999 and 2017, 702,568 deaths resulted from overdoses in the United States and 56% of these deaths resulted from opioids (Scholl et al., 2018). In the USA in 2016, drug overdoses killed 63,632 people, 66% of which involved opioids (CDC, 2018). In 2017, the deaths from overdoses increased to 70,237. There was an increase of 9.6% from 2016 to 2017. About 68% of the drug overdoses in 2017 involved opioids (Scholl et al., 2018). For 2016 and 2017, our society reached 19.8 overdose deaths per 100,000 and 21.7 per 100,000, respectively (i.e., the age-adjusted rate) (CDC, 2018a).

Rates of Overdoses of Workers at Workplaces in the USA: Imagine discovering at work that not only has one of your colleagues been consuming opioids but has died at work after overdosing. An ambulance is called, but it is too late! The impacts at your workplace would likely be drastic. Productivity would lower, emotions would run high and the work-life balance at your workplace would temporarily run awry.

At workplaces in the USA, unintentional overdoses due to the nonmedical use of drugs or alcohol increased 25 percent from 217 in 2016 to 272 in 2017. At workplaces around the USA, drug overdoses from non-medicinal or non-alcoholic substances reached 217 in 2016, which is an increase of 52 from 2015. 2017 was the fifth year in a row in which unintentional overdoses led to deaths at workplaces in the US where there has been an increase of at least 25 percent (BLS, 2018, p. 1).

The Potential Use of Suicidal Expressions by People Who Are Not Suicidal:

Manipulation through Pretend Cries for Help

Is there a time period when one should treat the expression of the desire to commit suicide differently than as a behavior leading toward suicide? When you are at the workplace or speaking to a co-worker, it is always important to take the expression of the want to commit suicide seriously. There is a need for the person to speak with someone about what he or she expresses as the desire to commit suicide.

When someone talks about committing suicide, there is reason to consider the person to be serious. There are cases where one begins talking about his or her own suicide briefly as a way to gain immediate attention and sympathy from the other and also as a way to manipulate his or her conversation partner. Talking about suicide can be a way to control a conversation. However, the question that we must ask ourselves is whether the person has suicidal thoughts that could lead to that person’s suicide.

First, it is best to inform the person that, if he or she is serious about suicide, you are available to communicate with him or her about it so that you can prevent it. However, if the expression of the desire to commit suicide is completely isolated, meaning that it does not involve any of the urgent situations or the serious risk factors mentioned above, then it remains a possibility that the person has used the expression of the desire to seek extra attention or sympathy. Moreover, seeking attention or sympathy by expressing such a desire can be extremely manipulative.

It is important to find out what the intentions or motivations of the person are and to express the seriousness of the expression of such an act. At the very least, you should ask pertinent questions regarding the expression of the will to commit suicide. Are you in pain or anguish? Do you have a way to commit suicide that you have thought about? Is there a situation in your life that makes you think about it more often?

Taking an interest by assessing the situation and asking relevant questions can serve to prevent suicides from happening. If you are in the USA, and someone is considering suicide, then have them contact people who can help, such as the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline and website.

We apologize to you for not having a toll free line that is international and helps reliably with your mental health, but we offer you some resources from the CDC and wish you the best in your life. Please read the “The Fable of the Economist”, and take an interest in knowing why you are so valuable to us all.

Citation of the article above: Brant, William Allen. (2021). “On the Prevention of Suicidal and Self-Destructive Behaviors and Danger at Workplaces.” Ethical Conflict Consulting. Suicide and Risk Prevention at Work. October edition. https://ethicalconflictconsulting.com/conflict-management/suicide-and-risk-prevention-at-work/

Resources available to help prevent suicide and promote mental health

CDC Resources:

- Suicide Prevention:

- visit the new webpage on Suicide, Suicide Attempt, and Self-Harm Clusters for information about suicide clusters, how to report them and how to get assistance

- access the recently updated Suicide Prevention Resources for fact sheets, publications and data sources

- access our fact sheet on suicide prevention

- Read the report on the State of State, Territorial, and Tribal Suicide Prevention

- Read the #BeThere feature to learn more about how you can help prevent suicide

- Visit our webpage on Coping with a Disaster or Traumatic Event for tips on how to take care of your mental health during an emergency

- States and communities can use Preventing Suicide: A Technical Package of Policies, Programs, and Practices to identify strategies and approaches with the best available evidence to prevent suicide

- Learn more about WISQARS data visualization: Leading Causes of Death: Suicide and Suicide Data by Age Group

Other Helpful Resources:

- Visit BeThe1To.com for information on how to talk to someone who is thinking about suicide, and information about how to stay connected during times of physical distancing

- Seize the Awkward provides tools, tips, and resources for how to have a conversation about mental health and suicide

- You can text or connect someone who is struggling to the CrisisTextLine. Text HOME to 741741 to connect with a crisis counselor 24/7

- The Trevor Project provides crisis support and suicide prevention services to LGBTQ youth

- The Veteran’s Crisis Line provides caring, qualified responders to help veterans in crisis; call 1-800-273-8255 and press 1, or text 838255

- The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) provides a Behavioral Health Treatment Services Locator

- The Disaster Distress Helpline (1-800-985-5990, available 24/7/365) provides behavioral health resources for communities and responders to help them prepare, respond, and recover from disaster

Join @CDCInjury in September for a Twitter Chat:

|

Need Help Now? Know Someone Who Does? Contact the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (1-800-273-8255) or use the online Lifeline Crisis Chat.

Both are free and confidential. You’ll be connected to a skilled, trained counselor in your area.

New CDC Report Shows the 2019 Cost of Injury

|

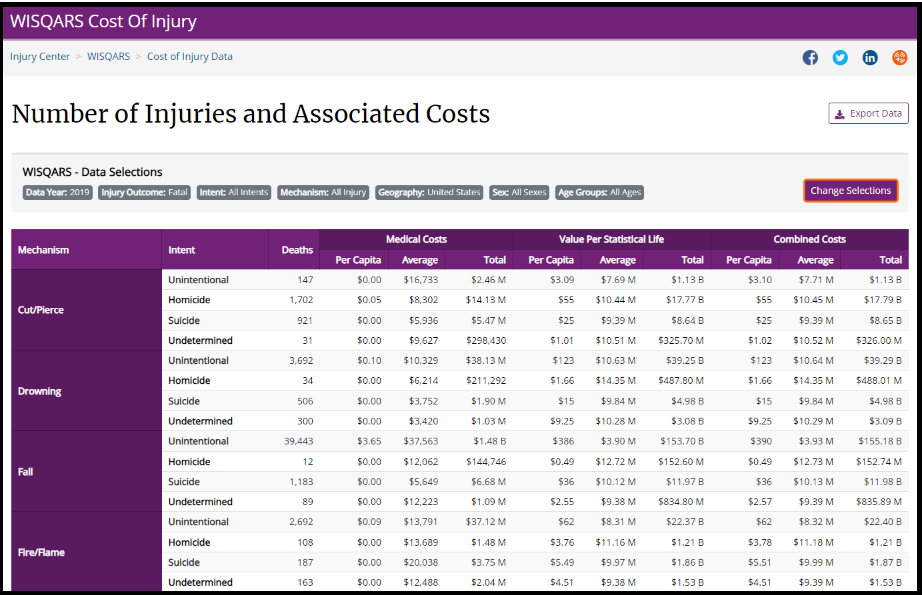

The 2019 cost of injury in the U.S. was $4.2 trillion, according to a new report in CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. The costs include spending on health care, lost work productivity, as well as estimates of cost for lost quality of life and lives lost. The economic assessment includes leading causes of injuries, such as overdoses, motor vehicle crashes, falls, suicide, and homicide.

A separate report estimates the cost of fatal injuries for states. The states with the highest per capita 2019 cost of fatal injuries were West Virginia, New Mexico, Alaska, and Louisiana. The states with the lowest fatal injury costs were New York, California, Minnesota, Nebraska, and Texas. All states face substantial avoidable costs due to injury deaths. |

|---|

|

|

|---|

|

Key Findings Fatal and nonfatal injuries are costly:

The $4.2 trillion cost of injury includes:

|

|---|

|

The cost of injury varied by sex and age:

You can learn more about what CDC is doing to prevent injuries and violence by visiting our Injury Center webpages. Fatal and Nonfatal Cost of Injury Data You can use WISQARS to explore data on fatal and nonfatal cost of injury:

Select a filter, such as data year, age, and geography Compare costs by mechanism and intent of injury Save and share cost data files

You can find more information on our Economics of Injury and Violence Prevention web page. |

|---|